What I wanted to learn more about was the curiously named group of photographers called the Photo Secessionists. I listened to Jeff Curto's History of Photography Class 9 Spring 2011 to find out more.

In its early life, photography wasn't sure what it was to do with itself. Was it art or commerce? It tried to be art by mimicking styles, look, subject and composition of painters.

Pictorialism was the name given to an attempt to make photography an art and be taken seriously. The subject matter came second to the finished product. Manipulation was common to try to achieve the look of a painting and to produce something that didn't actually exist. Fictional stories were reproduced in images and multiple negatives were used to create fantasies, or recreations from mythology or the Bible.

Peter Henry Emerson, an iconoclastic photographer in a way, wanted honest depictions of real people and spoke out against 'art' photography. He even used processes and slightly out of focus techniques to simulate what he considered a more realistic view a normal person's vision. His beautiful images from the Norfolk Broads in England:

If I have understood the thinking behind the Photo Secessionists correctly, Alfred Stieglitz wanted to combine the realism Emerson spoke about but produce pictures that were not only realistic, of the moment and often technically superb, but had a deeper meaning and were also beautiful prints. What was in front of the camera was less important. What was important was to break away from the narrow rules and customs of the day.

He was also one of the first to just print part of the negative and he often used small cameras, relatively speaking of course. He also managed to produce stunning night time shots when taking the basic technology at his disposal into consideration:

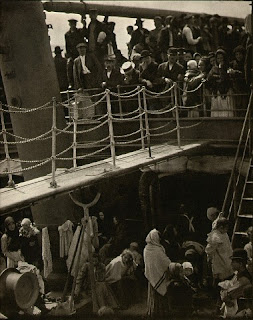

Some more examples of his work:

Not only was Stieglitz an influential photographer, he was also a promoter of American photographers. He set up a yearly salon and the group, Photo Secessionists. The idea behind the secessionists was to break away from photography of the past and make photography its own thing, to change thinking about what constituted a photograph. He wanted to advance photography to a higher artistic form and make an active protest against the old thoughts on photography and, perhaps more controversially, the dictatorship of the entrenched institutions, galleries, art schools and professional art organizations that enforced or at very least sanctioned copying or imitation. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photo-Secession)

Some examples of work by Photo secessionists:

Gertrude Kasebier:

Edward Steichen:

Clarence White:

Alvin L Coburn:

Anne Brigman;

Robert Demachay:

So there you have it, a short introduction to the Photo Secession movement which I hope may stimulate you to find out more.

Thanks again to Jeff Curto's History of Photography.